RAT’s: Nature’s Little Access Brokers

All breaches start from something. This can be as simple as compromised credentials leading to the initial access via the SSL_VPN or RDWeb, or as complex as custom malware loading and executing the next payload in memory of an internal device. A common trend observed by the Blackpoint SOC is the utilization of Remote Access Trojans (RATs) for initial access into a network.

These RATs are deployed via various techniques including drive by downloads, phishing emails, fake Captcha’s, amongst other mechanisms. Once this malware is deployed on the host, it calls back to the attacker infrastructure, providing access to the internal network.

Key Findings:

- Threat actors continue to leverage Remote Access Trojans to gain initial access into networks

- These RATs provide a threat actor access to the internal environment. The infected host is leveraged as a jumpbox between the breached network and attacker infrastructure.

- Threat actors will drop custom malware, credentials, and enumerate their access to see how they can move laterally

- These RATs come in all shapes and sizes, including leveraging legitimate applications to execute malicious payloads.

Examining the Attack

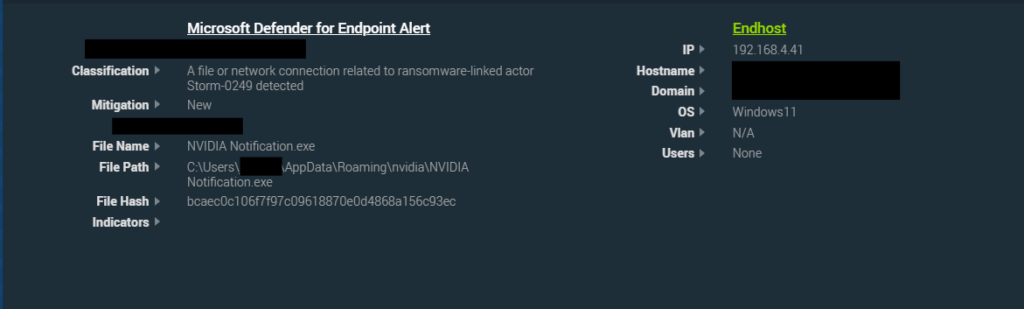

The Blackpoint SOC recently responded to an intrusion within a Communications based organization, where initial access stemmed from the deployment of a RAT on an end host.

The RAT deployed onto this host leveraged a legitimate and signed NVIDIA binary called “NVIDIA Notification.exe”. This binary is a legitimate part of the NVIDIA driver suite, whose main function is to help manage and deliver notifications tied to the NVIDIA software installed on a host.

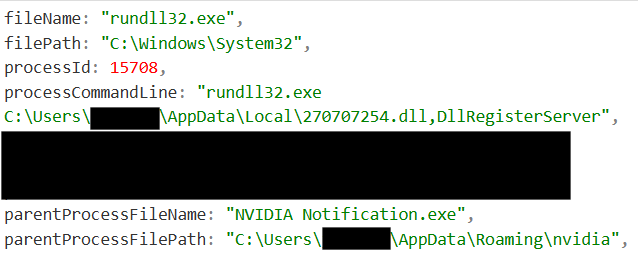

In this case, this binary was dropped within %APPDATA%\Roaming\nvidia and was leveraged to sideload and execute a malicious dll called 270707254.dll. The execution of this dll results in the execution of this RATs malicious payload, which leads to the callout to the attacker-controlled infrastructure.

Enumeration

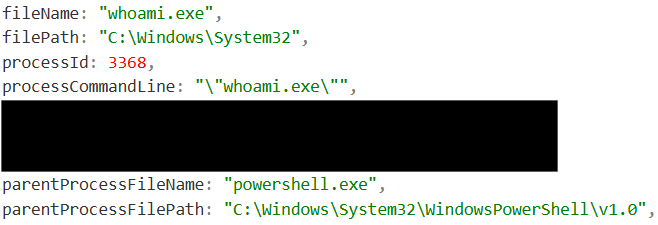

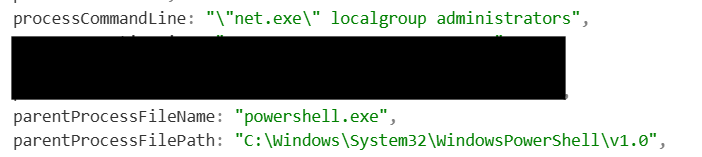

Once the threat actors had access to this device via their RAT, they then began enumerating characteristics of this environment. This enumeration focused on fingerprinting the Active Directory environment as well as the current user / host. These enumeration efforts focused on identifying:

- Current user and privileges

- System information about the current device

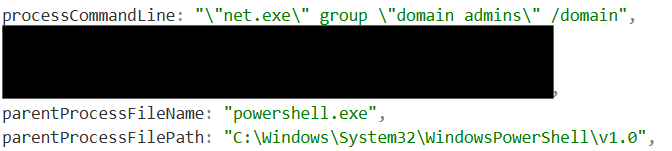

- Domain Administrators within this network

- Local Administrator on the infected device

- Domain controllers in this network

- Domain Trusts

- IP’s associated with the Domain Controllers

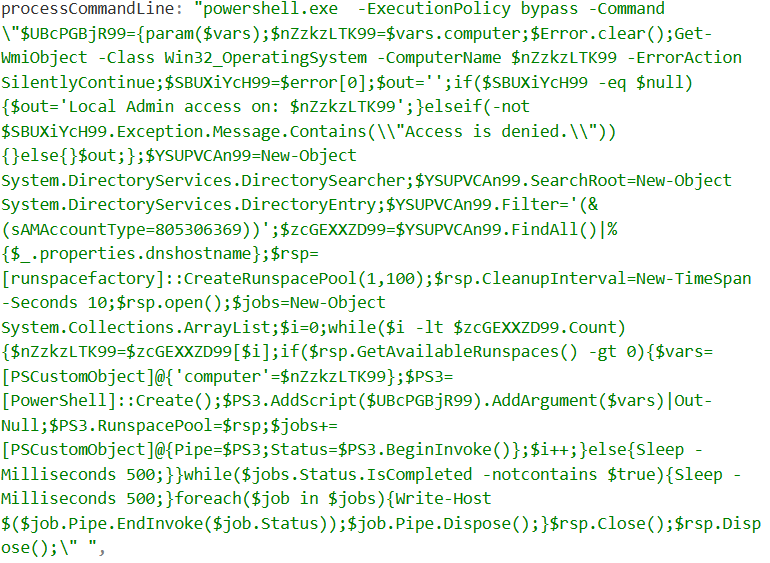

The threat Actor also ran two interesting PowerShell scripts. The first script focused on identifying what devices within this network they have local administrator access on. Identifying these devices provides the threat actor with a valid route for lateral movement as they move along their kill chain.

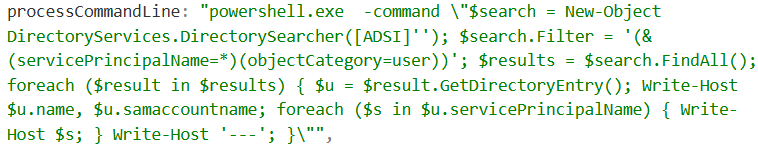

The second PowerShell Script identified accounts with Service Principal Names (SPNs) within this network. The process of identifying accounts with valid SPNs is typically the first step within a KerbRoasting attack

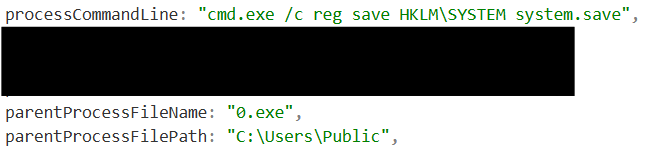

After actively enumerating this environment, the threat actor then began to drop files on disk as well as dump credentials on the infected host. Two binaries called 111.exe and 0.exe were dropped within C:\Users\Public.

0.exe appears to be leveraged to spawn an elevated command prompt to dump the SYSTEM hive on this device and save its output within “system.save”. The dumping of SYSTEM provides the threat actor with the necessary information needed to dump the password hashes stored in the Security Account Manager (SAM) hive. On top of dumping the applicable registry hives, the threat actor also dumped the credentials stored in browser on this host.

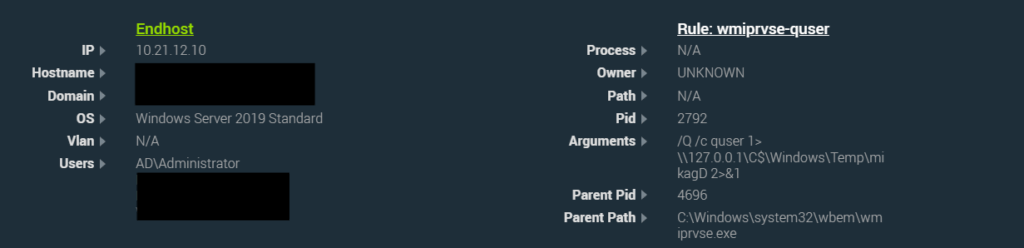

During this entire enumeration and exploitation phase, the threat actor obtains access to the domain administrator account. Using this domain administrator, the threat actor utilized wmiexec to run quser on both Domain Controllers within this environment.

Image 11 – Use of wmiexec to run quser on domain controller

Wmiexec is a tool within the impacket suite, that allows for remote code execution via Windows Management Instrumentation (WMI). The threat actor then used quser, a built-in Windows command-line utility, on these hosts to identify the users currently logged into the devices.

Conclusion

All this observed activity demonstrates how dangerous initial access-based malware can be. The accidental installation of a RAT can rapidly escalate from a single compromised endpoint to a full domain compromise, often within minutes or hours. Like their namesake, Remote Access Trojans are similar the rats in how they operate, not only are they lurking in the background, but leading to deeper infiltration and far more significant issues if not addressed immediately.