Lateral Movement

In the cases involving this threat actor, lateral movement occurred from unprotected devices, limiting the ability to determine the factors for initial access. Each of the monitored cases involved multiple attempts to propagate laterally across the network. The two techniques observed were T1021.001, Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP) and T1021.002, SMB/Windows Admin Shares. In both cases, the threat actors used valid stolen credentials and, upon gaining access, used them to begin the next stage of their campaign: deployment of enterprise software.

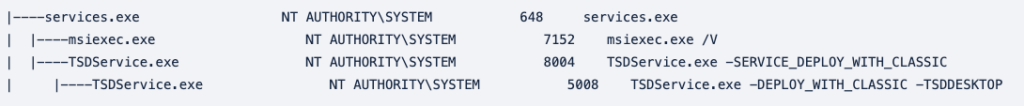

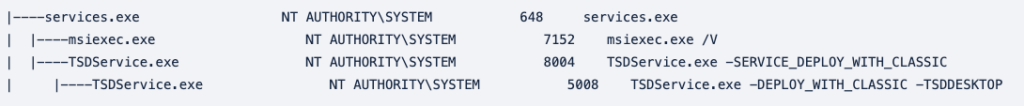

Total Software Deployment (TSD) is a software management tool that enables remote deployment. Unfortunately, the features that make this an appealing tool for use by Managed Service Providers (MSPs) and Information Technology Service Providers (ITSPs) also make it an appealing tool for threat actors (see Figure 1). One of two key features of this tool is that it can deploy packages in ‘unattended mode’ which will not interrupt end users. The second key feature is that TSD scans the network automatically and, using the admin password, inspects every device. A more robust version of the network scanning capability, Total Network Inventory (TNI), has also been observed. This is another software from the same creators of TSD with the key observable difference being TNI will also document the hardware on the endpoint, not just the software. Nevertheless, it does lack the capability of TSD to deploy software packages.

Figure 1: TSDService

Not only can TSD scan endpoints and install software, it can also remove software from an endpoint. An example would be anti-virus (AV) solutions. Fortunately, most AV solutions have anti-tampering to prevent this, but does this consider when the credentials are from an administrator? In this instance, TSD is not just a lateral movement tool, but a reconnaissance tool as well as a, albeit limited, device controller.

Device Control

In each of the identified cases, Blackpoint observed that the first software package deployed was another enterprise capability often used by MSPs called ScreenConnect, also known as ConnectWise Control. Designed to offer help desk-style services, this tool allows for full remote control of an endpoint. ScreenConnect has two main features appealing to threat actors. The first is known as ‘backstage mode’ which allows for complete access to the Windows terminal and PowerShell without the logged-on user being aware. This is the primary use case observed by Blackpoint. The second is a mass-deployment feature for the agent based on the subnet or ARP table. While this is a similar feature to TSD, this tool allows for another avenue of lateral movement. Blackpoint has yet to see attackers use this feature in earnest.

Since TSD is automated, the scanning of devices and the deployment of this tool occur very close together. When access is obtained, ScreenConnect is then able to issue further commands such as running PowerShell commands to download malicious payloads or ensure persistence using Registry Editor (regedit). Fortunately, in all examined cases where devices were monitored, Blackpoint was able to prevent any such capabilities from being run.

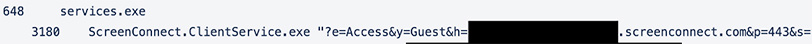

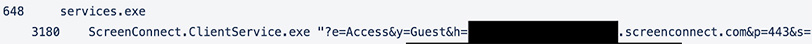

For each session of ScreenConnect that is run, a set of URL-encoded ‘Client Launch Parameters’ [1] (see Table 1) are used to initialize it (see Figure 2).

| Name |

Variable |

Description |

| SessionType |

e |

The type of session

(Support, Meet, or Access) |

| ProcessType |

y |

The session’s participant type

(Guest or Host) |

| Host |

h |

The URI used to reach the server’s

relay service |

| Port |

p |

The port on which the relay

service operates |

| SessionID |

s |

The GUID used to identify the

client to the server |

| EncryptionKey |

k |

The encryption key used to

verify the server’s identity |

| SessionName |

i |

The name of the session as it

appears on the Host page |

| CustomProperties |

c |

The value of any pre-defined

custom properties |

| NameCallbackFormat |

t |

The value the client tells the

server is the name of

the session |

|

Table 1: ScreenConnect Client Launch Parameters

Figure 2: ScreenConnect Service

In each case observed, certain parameters were always the same. Each session was an Access session with process type Guest. These parameters combined are vital to giving threat actors access to the targeted device. In this instance, the relay server observed had been obfuscated. In the documentation provided by ScreenConnect, they suggest changing the port value to something such as 8041. Interestingly, every malicious threat instance observed uses the default parameter of 443. This is not surprising if it is assumed the intent of the actors is to use out-of-the-box tools with minimal interaction. In all observed cases of ScreenConnect, both legitimate and malicious, there is no observable use of the SessionName, CustomProperties, or NameCallbackFormat.

Post execution of the ScreenConnect Client Service, the next step is to assign roles to the instance. By default, there are two roles, administrator and host. These, on the endpoint, appear to be identified as ‘System’ and ‘User’ respectively. Evaluation of legitimate- and benign-use cases of ScreenConnect suggests that only the malicious instances call both the ‘System’ profile and the ‘User’ profile (see Figure 3). Instances of legitimate use appear to only call one or the other.

Figure 3: Roles and Permissions

After the assignment of both roles, two further behaviors have been identified. Firstly, the threat actors utilize reg.exe to alter the WDigest registry. By setting the value of “UseLogonCredential” to 1 (see Figure 4), Lsass.exe will retain a copy of the user’s plaintext password in memory. Note, this is being done on every device concurrently as ScreenConnect is being propagated. Secondly, the threat actor conducts further enumeration of devices within the compromised network.

Figure 4: Manipulation of WDigest registry key